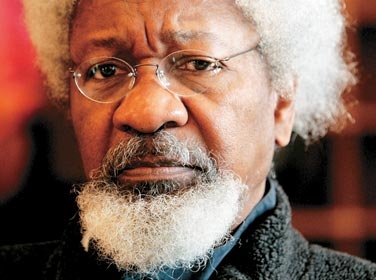

There has been widespread criticism both inside and outside Nigeria of the way this latest attack by Boko Haram has been handled by President Goodluck Jonathan and in general how his administration has faced the challenge of terrorism. But few people have been as pointed and persistent as my next guest, the Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka, whose critiques have previously landed him in jail. As well, many consider him the voice and conscience of his country, so we thought this was an important moment to speak with him. And he is with us now. Professor Soyinka, welcome to the program. Or welcome back, I should say. Thank you for speaking with us.

WOLE SOYINKA: Not at all. Thank you.

MARTIN: It's been a month, as we said, since we learned of the attack on the girls' school. And you have said that this is a defining moment for Nigeria. Why do you say that?

SOYINKA: Well, it's straightforward, actually. Nigeria has been under the throes of this insurrection for a number of years. But it didn't really begin with the recent spate of killings. It's been there. What I called the Boko Haram mentality has been undermining the sense of community, the sense of nationhood in Nigeria for years, long before the world heard about it.

I'm talking about the mentality and the – almost the culture of impunity, in which people of one religion have been able, at a drop of the hat, at some imaginative slight, gone on a rampage and slaughtered – slaughtered fellow Nigerians, for no reason other than some real or imaginary felt slight on their religion. And they've done this over and over again, without any consequences, within schools, within streets, in markets, no matter where. And so this has been the buildup where a section of the nation finally reached the point where it felt it is the right for it to demand the Islamization of the entirety, beginning from the president.

MARTIN: The government has been widely criticized for doing too little, too late to respond, not just to this attack, but previous ones that have not gotten as much attention. I do want to mention, at this point, that we have repeatedly invited representatives of the Nigerian government to speak with us over the past weeks. We do hope that they will join us at some point, but they have yet to make a representative of the government available to us. I do think it's fair to say that. But where do you think the government went wrong? I take it it's not just in response to this particular event.

SOYINKA: You're quite right. It's politics. It's been opportunism. In other words, I'm talking about some politicians who are so power-hungry that they're willing to sacrifice, not just lives, but even the existence of the nation by exploiting religious sentiments, very often, warped, distorted reading of the Quran – and I'm speaking specifically of Islam – as you know Boko Haram makes no bones at all about wanting to Islamize the nation. And when politicians, especially in our part of the country, have a contest – power contest among themselves, even or even against the center or the areas of the nation, they evoke the most dangerous religious sentiments.

I'll give you an example. Zamfara, one of the poorest states in the nation – when the political struggle for Zamfara began, the governor, who was later proved to be an incorrigible pedophile, he invoked Sharia just to obtain votes and come into power. He said if he came to power, he would impose Sharia on that section of the nation. And of course, it went ahead, he did and other nations followed suit. Now, this has been the failure of the center to say, firmly, the constitution does not permit a theocratic state in the nation. Boko – sorry.

MARTIN: So you're saying this is not just simply a failure of the president. This is a – what? – how would you describe it, a failure of political leadership overall?

SOYINKA: It's been a tendency. It's not just a failure of this president. It began several years ago. It began nearly a decade and a quarter ago, I would say, when political expediency overrode even common constitutionalism.

MARTIN: If you're just joining us, I'm speaking with the Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka. We are talking about recent events in Nigeria. You've described this as a global crisis. In fact, you have said that people should put aside their false pride and accept whatever international aid is offered to address the specific crisis involving the girls. But, you know, more broadly, what do you think would be helpful at this point?

I mean, if you're talking about a broader failure of political leadership, you know, how do you get that genie back in the bottle? How do you write something that you're saying – you've previously described kind of religious extremism as a virus. And how do you address that, if it's not just one person's failure, but it's a system failure at this point?

SOYINKA: I would like make a comparison. I've made it before. I want to go a bit deeper into it. Take the siege of Bethlehem. Obviously, that is a little bit of an international global history, which should be on the minds of everybody. And what is happening here – the kidnapping of 200 students – is, for me, different only in terms of environment and circumstances from the siege of Bethlehem, where schoolchildren were sacrificed to the religious extremism of Mr. Baladev (ph) or Baidiev (ph) – I can't remember now – even though, of course, this was also part of Chechen separatism. But the driving force that sacrificed and that traumatized the, you know, youthful humanity was basically religious fundamentalism.

So when it happens in a country like Nigeria – you have forested areas and all that. That's the only difference. The world should wake up to the fact that we're speaking of a phenomenon which doesn't belong to only one country and mobilize to terminate it once and for all. Well, that's an exaggeration. It'll never be completely terminated, but at least, to control it, to come together to punish those who use religion to separate humanity and traumatize one part of it.

MARTIN: Do you think the first priority would be – what? – to secure the – well, to that end…

SOYINKA: Yes.

MARTIN: …Though, the whole question of negotiating, I wanted to ask you about, you know, the government. There's this question – as you say, the leader of this group says that he will exchange these girls for his imprisoned, you know, fighters. And the government said – much of the international community is absolutely opposed to this. The government says it will not negotiate. Do you think that's the right stance?

SOYINKA: Well, it's a difficult question for me because there's a subjective aspect and there's the objective aspect. We know very well that the priority in the minds of all of us is to get those children out unharmed. And in the process, governments have to make very difficult decisions. Subjectively, I don't even want to hear the word negotiation. I just want those monsters exterminated.

Well, then I know that there are people – those who are in the position to make difficult decisions are blind to do so, sometimes pragmatically. But it has to be done – if there are negotiations, it has to be done in a way in which it is clear to such criminals that there is a bottom line, that there's certainly certain basic moral laws which will not be flouted.

MARTIN: Forgive me if this seems trivial in contrast to these much bigger issues that we are facing. But many people have undertaken this hashtag #BringBackOurGirls because they want to show solidarity with these girls and to show that it does matter to them. And there's been some discussion about whether this is trivializing the issue or whether it is an important stance to say that the global community stands united against this. May I ask your thoughts about this?

SOYINKA: Well, I happen to have been a part of that – of the evolution of that slogan, which is a very – for me, is a mobilizing – it doesn't matter what it is. We say mobilize people's awareness and consciousness and also commitment. It's not trivializing the issue at all. And the – especially on the African continent – in the African continent, it's a primarily our responsibility, even historically.

And let me explain this. Where here, in the United States, the land is called the land of the free today, but it was the land of slaves. And we have a vicarious connection with the black population – the African-American population of this nation. And Africans should be able to say, first of all, the very notion of a section of our humanity being treated as sub-humans – the way womanhood is being treated by these fundamentalists, that it becomes a the primary responsibility to repudiate such thinking.

We're talking about the period where, for a black man to be caught reading – to reveal himself as being capable of reading, it meant he was either amputated or castrated or even hanged. And so for any African with any sense of memory at all – or, as I said, vicarious kinship with ex-slaves – to accept the dehumanizing of womanhood because of the gender, when we have this history in the back of our minds, for me, it's totally abominable and unacceptable. And so Africans should really be the ones to propel this movement around the world, bearing in their mind our own history.

MARTIN: We only have about a minute left. Is there anything else you would wish us to be thinking about in the days ahead? A final thought for us, please.

SOYINKA: Just to reemphasize the fact that it doesn't matter where the help comes from. We've got to accept it. We've got to invoke it. We've got to plead for it. Even the Soviet Union, we must talk to them and say, what did you do wrong that these children perished in an inferno? What would you do now? So the false pride aspect has got to be abandoned completely.

MARTIN: Wole Soyinka is Nobel laureate. He is a prolific and wide-ranging writer. We were able to reach him at his studio in Claremont, Calif. Professor Soyinka, we thank you so much for speaking with us. And we do hope we'll speak again, hopefully under happier circumstances. Thank you for coming.

SOYINKA: Thank you.