"When I traveled from Atlanta to Washington, we drove straight through," Julian Bond said of his journey to the nation's capital for the march. Bond, chairman emeritus of the NAACP and a professor at both the University of Virginia and American University, was raised in Jim Crow-era America, when laws both official and unspoken dictated travel conduct.

At the time, Bond, a 23-year-old activist working as publicity director for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, was traveling via car with friends from his organization. Although King's legendary speech on the need for racial equality awaited them, Bond's reality as he traveled to Washington could not have been further from the reverend's vision.

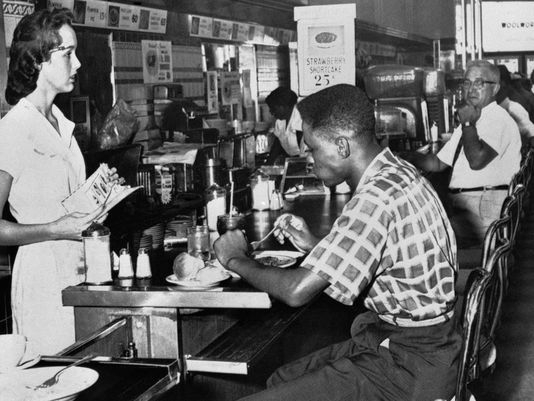

In the 1950s and early 1960s, travel was a complicated endeavor for blacks. The landmark 1954 Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education outlawed segregation, and the Interstate Commerce Commission, in response to the Freedom Rides, banned segregation at interstate travel facilities in 1961. Still, integration was rare, particularly in the South.

Restaurants, hotels and gas stations blatantly denied service to blacks. Travelers like Bond and his black SNCC colleagues were just as susceptible to these restrictions — if not more so, because of their civil rights agenda.

"You knew that when you traveled, white people could treat you any way they wanted to, and there was nothing you could do about it," Bond said.

While en route to the march, Bond remembers, he was denied use of gas station restrooms, a barrier not faced by his white peers in the car.

"When we were driving along and (one of us blacks) had to go to the bathroom, nine times out of 10 we had to pull over to the side of the road — we couldn't use a gas station," he said.

Segregation made travel for blacks not only logistically difficult, but often dangerous.

If African Americans entered a city or neighborhood where they didn't appear to belong, the locals would often make it known, such as by refusing them service or even chasing them out of town.

The Negro Motorist Green Book, published in 1936 by Harlem postal worker Victor H. Green, eased some of these concerns. Green, an African American, created the book as a way of providing New York blacks with information on stores that would cater to them, but he later expanded its content to include hotels, restaurants, museums and parks.